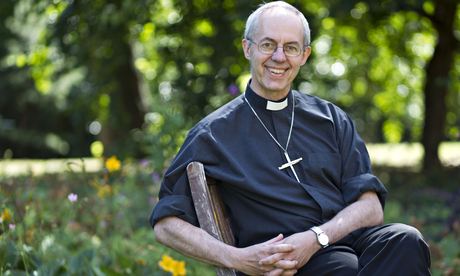

Justin Welby

now looks like the best archbishop of Canterbury the Church of England

could possibly have, but when he was appointed he was almost unknown,

and had only been a diocesan bishop for nine months. What got him the

job – after he had made the shortlist – was that he was the only

candidate who did not deny or flinch from the internal research

suggesting that the church would dwindle, on existing trends, from about

one million committed members to 150,000 by 2050.

His first year

in the job has been marked by tremendous energy and rather more physical

and moral courage than is expected of an archbishop, but there is a

tremendous sense of urgency underlying this display.

He has already had two notable successes, and one of them will last. He has led the church past the

General Synod's traumatic failure to approve female bishops in 2012, so that it seems certain that some will be appointed next year; and in the summer

he managed to get the whole country talking about loan sharks and thinking of the Church of England as an organisation more concerned with the evils of payday lending than of sex.

He denounced payday lenders as evil in the

House of Lords. Within a day the

Financial Times discovered that the church itself had an indirect investment in Wonga through

a fund in which its pension fund invests. Welby was furious when he

discovered this but in public, on the Today programme, simply and

disarmingly admitted it was a mistake. The whole thing was an

improvisation that did him a great deal of good. His bold statement that

the church could instead invest in credit unions that would "compete

Wonga out of existence" was never really tested. What got through was

the unmistakable sincerity of his rage and pity for the victims of such

lenders and his determination to do more than seems possible, even if

it's much less than is needed.

He has not been able to heal the

international schism over homosexuality, which has, if anything, grown

worse in the last year. The archbishop of

Nigeria,

Nicholas Okoh, who was an enthusiastic backer of a law that makes it punishable with a jail sentence even to talk about

gay marriage, said recently: "Women are not scarce, men are not scarce and God has made adequate arrangement for human

sexuality,

so anybody who is developing any extra sexual instinct or desire, I

think such a person should attend to himself because there is something

wrong."

Link to video: Justin Welby: Wonga investment should not have happened

'An executive type'

Only a tiny minority of members of the

Church of England would say things like that, although some would only

regret Okoh's lack of ambiguity. Welby might have been one of them 15

years ago but he has changed since then, and he understands that the

country has changed too. He will not be able to hold on to the

Nigerians, or the Church of

Uganda,

another enthusiastic backer of homophobic laws. But he is making

strenuous efforts to hold together as much as possible of the remains of

the Anglican Communion, although there is no longer any pretence that

this is a coherent body with discipline and doctrines of its own. One of

Welby's closest advisers dismissed that idea as "a Roman Catholic

fantasy".

That's only one of the sacred cows he has been

slaughtering. In many respects, he has behaved like a business

executive, with, in private, a remarkably hard-nosed realism no matter

how uplifting he has been in public. "He's definitely an executive

type," says one senior colleague. "He thinks in those terms. He operates

in those terms. He's willing to make quite big moves."

The most

obvious example of this dynamism was his recovery from the synod's

fiasco over female bishops in 2012, when legislation that would have

made it possible to choose women as bishops was blocked by a rump of

conservative evangelical lay people, elected through an arcane system of

committees that ensured they were wholly unrepresentative. Welby's

reaction was threefold. First, he co-opted a number of senior women on

to the committees previously reserved for bishops, so that they had

access to real power. He pushed the synod into drastically shortening

its timetable for legislation, so the mistaken vote could be undone in

two years instead of five. And he set up a process of reconciliation and

informal face-to-face negotiations between supporters and opponents.

None

of this might have worked without the shock and revulsion felt in the

wider church – and in parliament – at the failure of the earlier

legislation. But this reaction would not on its own have shaken the

defences of the conservatives, who were still resisting last summer.

Only the personal and institutional pressure that Welby applied had that

effect, and by February this year the opponents had accepted a much

worse deal than they had earlier rejected, yet seemed happier about it.

This was not entirely because accepting inevitable defeat meant they

could continue to wrangle about gay clergy for the foreseeable future.

When

first chosen, it seemed the most notable thing about Welby was that he

had been a successful businessman: a man who understood money and could

chastise bankers in their own language. But looking back after his first

year, the most notable thing is less his civilian job than his

formation in the peculiarly English upper-class

Christianity

of Eton, Cambridge and Holy Trinity Brompton (HTB). These are the

places where Christianity is still part of the culture in a way that

just isn't true elsewhere.

Welby's background was a startling

mixture of privilege and insecurity. On his mother's side he was

descended from five generations of colonial administrators. She had been

a secretary to Winston Churchill; among her close relatives were Lord

Portal, who ran the RAF, and RA Butler. His stepfather was a

distinguished theologian. But his father, who soon divorced his mother,

had only appeared to be an Englishman called Gavin Welby. In fact –

unknown to his English family – he was born in a Jewish-German immigrant

family called Weiler, made his first fortune bootlegging in New York

during prohibition, and died an alcoholic who had left the last two

years of Welby's school fees at Eton unpaid.

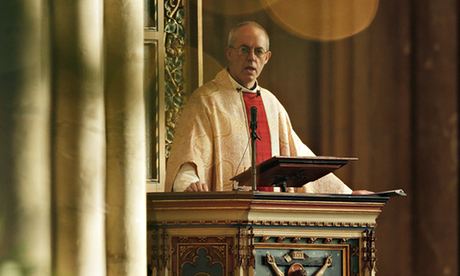

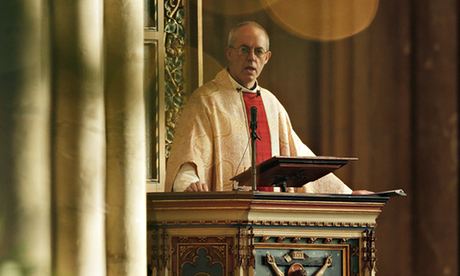

Welby delivers his Christmas Day sermon at Canterbury cathedral last year. Photograph: Matthew Lloyd/Getty Images

Welby delivers his Christmas Day sermon at Canterbury cathedral last year. Photograph: Matthew Lloyd/Getty Images

Gavin Welby was a figure of enormous charm and energy, but entirely

unreliable and mysterious even to those closest to him. At Eton Welby

was not among the fashionable boys. He was much later described by his

housemaster with wonderful condescension as "a model boy, though quite

undistinguished". He was not a Christian then: he had had the

conventional upper-class socialisation of tedious hymns and meaningless

sermons, which normally functions as a vaccine against religious

fervour. But at Cambridge he was converted by an extraordinary group of

earnest upper-class evangelicals, who now, 30 years later, have taken

over the Church of England.

The group that later became the core

of the HTB movement was, from the outside, quite ludicrously posh. Five

of them, for example, were called Nicky and four of those had been to

Eton. They came out of a culture of clean-living, rugger-playing

manliness that seemed little changed since the first world war – in one

sermon preached at HTB in this century, the subject of oral sex was

dismissed with the words "Chuck it, men!" In fact, though, this had been

a deliberate anachronism planted in the 1950s and operating through

summer camps that recruited through the public-school network.

And

just as their tradition was a little bit phoney, so was their place at

the heart of the establishment. Three of the core group (Nicky Gumbel,

who more or less invented the Alpha course, Ken Costa, who became a

fantastically rich banker, and Welby himself) were partly Jewish, though

Welby did not then know his father's real identity. They had the

self-assurance to appear absurd, with their earnestness and the tracts

they handed out, but not, perhaps, the self-assurance to suppose they

deserved all their privilege.

Enthusiastic Christianity was

certainly not in the mainstream at Eton. The ungenial contempt of more

secular Etonians is nicely captured by an entry in

Alan Clark's diaries about

Michael Alison, a Tory politician who was also a churchwarden at HTB:

"Saintly but useless. You need someone with guile, patience, an easy,

fluent manner of concealing the truth but drawing it from others in that

job. It is extraordinary how from time to time one does get people who

have been through Brigade school, taken their commission and served,

seen all human depravity as only one can at Eton … and yet go all naive

and Godwatch."

In fact, the form of Christianity to which Welby

was converted as an undergraduate did emphasise the worthlessness of

unredeemed humanity. It wasn't really naive at all. "Guile, patience,

and an easy, fluent manner" distinguish Etonian Christians as much as

Etonian pagans. It's just that the Christians want to tell you the truth

as well.

Christian rebels

For a man with a well-deserved

reputation for honesty and straight dealing, Welby has said some

staggeringly untrue things – most famously

when he told Giles Fraser that he was "one of the thicker bishops in the Church of England".

He has an unforced relish in things of the mind – he loves the

efflorescence of Nigerian English for its own sake – but he is not an

intellectual. He doesn't build systems – he looks for what works.

Welby during a two-day visit to South Sudan. Photograph: Carl De Souza/AFP/Getty Images

Welby during a two-day visit to South Sudan. Photograph: Carl De Souza/AFP/Getty Images

But self-deprecation of that sort doesn't count as dishonesty when no

one (at least no one in the club) is meant to take it seriously, and it

is in any case flattering to all the other bishops.

The young

Cambridge Christians, so outwardly conventional, were in one respect

rebels against everything they had been taught. They embraced

wholeheartedly the charismatic revival – talking in tongues, miraculous

healing, fainting in the spirit, and even prophecies – all things

anathema to the older Calvinist tradition that was then dominant among

Cambridge evangelicals. Their teacher in this was a bear-like

Californian, John Wimber, who had been the drummer for

the Righteous Brothers,

and founded the immensely successful Vineyard group of charismatic

churches. Quite a number of people brought up in the emotional

straitjackets of the English upper classes found blessed relief in the

permission the Holy Spirit gave them to weep or laugh and gibber and

faint in public. In the mid-1990s, when the movement's influence on HTB

was at its height, I visited a Chelsea church run by Nicky Lee, one of

the men who converted Welby at Cambridge, and when the Holy Spirit

started knocking people down, I'd hear the distinct rattle of pearls

when the young women fainted to the floor.

This current of

life-giving absurdity electrified them and gave those earnest young

prigs the means to change over the years, even after they had become

successful. The Holy Spirit gave them permission to be weird, and to

navigate the collapse of traditional Christianity, which left an earlier

generation of evangelicals stranded in reactionary nostalgia.

Asked

what he had learned since his conversion, Welby said: "The longer you

go on, the more I realise the infinite and amazing and wonderful

diversity of human beings and what they do. Grace is at the heart of

Christian faith and not law. The church isn't principally about rules.

It's about a relationship with Jesus Christ, and he shapes people's

behaviour. The street pastors, helping people at 3am on a Saturday

morning who are drunk out of their minds, are not going to give them a

lecture about drink. They're just going to help them to get home. The

church is not a place where good people go. It's a place where bad

people go to meet God. It's a refuge for sinners."

When Welby left

Cambridge he dithered for a bit and then found a job working for a

French oil company, Elf Aquitaine. More importantly, he married Caroline

Eaton, a classics student at Cambridge, whose sister was for a while

the vicar's secretary at HTB: the networks remained incredibly tight. In

their summer holidays the couple went Bible smuggling together behind

the iron curtain. Caroline Welby still accompanies him on some foreign

trips, most recently a harrowing journey through the war zones of

South Sudan

and the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. On that trip, as he

later told the synod, they walked through a Sudanese town where 3,000

people had recently been killed. The bodies of 22 people from the

cathedral staff – murdered and, if women, raped as well – were waiting

for the archbishop to bury them in a mass grave. Yet he keeps going

back. He doesn't flinch.

From oil man to vicar

This life

is an enormous distance from the future he had when he was an oil man in

Paris – though that is where his visits to Nigeria started. The newly

married couple lived in France for five years. Their first child,

Johanna, was born there. When she was seven months old he was promoted

to a job in London, but on the journey in the car with Caroline they

crashed. Johanna was thrown clear in her carrycot and died in hospital

three days later. The Welbys went on to have five more children but the

experience of bereavement stayed with them. Welby's unofficial and very

evangelical biographer claims that Caroline Welby's immediate reaction

after the crash was that "maybe somehow she was at fault for not praying

hard enough before the journey".

This shows the way in which God

appeared to the young people of HTB as a permanent presence and

companion, with opinions on everything – an omnipotence somewhere

between a father and a nanny. Later, visiting a Vineyard church in

California, they came to a more balanced view. It is a very notable

feature of Welby's Christianity that much of it has been formed outside

the Church of England, both in the charismatic evangelical Vineyard

network, and later through contacts with Roman Catholics: he has invited

a Catholic community to live and pray full-time in Lambeth Palace.

Link to video: Justin Welby 'astonished' by archbishop of Canterbury appointment

After a year in London working for Elf Aquitaine, Welby was

headhunted by Enterprise Oil, a company formed to exploit the

privatisation of British Gas's North Sea assets. In the five years he

worked there as treasurer, it grew to be one of the 30 largest companies

on the stock exchange. By that stage, his salary was more than £100,000

a year. He threw it all in to become a vicar, and not even a

fashionable one.

He trained in Durham, rather than one of the

Oxbridge seminaries, then spent 15 years serving the Coventry diocese.

His energy, intelligence and experience marked him out for promotion

even in an organisation as sclerotic and short-sighted as the Church of

England can be. Coventry cathedral, because of its destruction by the

Luftwaffe in the second world war, has specialised in teaching and

practising reconciliation, and Welby was drawn into this work early on.

He travelled almost everywhere where Christians were killing or being

killed – he has made 70 visits to the dangerous regions of Nigeria, and

in 2003 made an overland dash to Baghdad from Jordan in company with

Andrew White, another HTB figure who became the Anglican vicar of

Baghdad. Several times he texted Caroline because he thought he might

imminently be killed.

Realism

From Coventry he moved to become the dean of

Liverpool

cathedral, a building emblematic of the Church of England's troubles:

it stands gigantic, architecturally remarkable, largely empty and almost

broke in an indifferent and rather hostile city. He sorted the finances

within the first three years. Cathedral attendance went up, as

attendance in almost all cathedrals has done in the past 10 years. He

had the bells play John Lennon's anti-theist song Imagine as part of an

arts festival, which shocked some people but helped to restore the sense

that the cathedral was connected to the city's imagination.

When

he was promoted to be bishop of Durham, one of the church's most senior

posts, few were surprised. But his approach was astonishingly effective

and free of pretension. At the time he said: "The longer I go on with

this, the more I realise that the Church of England is not an

organisation in any recognisable sense. Because bishops are dressed up

in funny clothes, with funny hats and special sticks, it's assumed that

if they say to a bunch of parish clergy: 'Do something,' they will do

it. But that's not how it works and never has been."

Within months

he had circulated a document in the diocese saying that without realism

about finances the whole thing would collapse within 15 years. He

urged, and put through, a reform of the funding system in which parishes

were allowed to decide for themselves what they could afford to pay the

central authorities, instead of being assessed. On the other hand, they

would be expected to pay what they had honestly promised. Currently,

40% of them do not.

This kind of realism has carried through to

his time in Canterbury. He works there in small groups of no more than

six or seven, which debate decisions thoroughly before they are taken.

He quickly culled the old guard at Lambeth and appointed an eclectic

team, including, Jo Bailey Wells as his chaplain, who had been working

with her husband in the US for eight years when chosen. He is by nature

impetuous says one well-placed observer, and this way of working is a

deliberate check on his temperament. But once decisions are taken, they

are driven through effectively. One of these groups is planning a huge

cull of ecclesiastical regulations. The aim is to make it much easier to

plant new churches, reopen old ones, and close down those that can no

longer be sustained. "That sort of thing needs to change very

dramatically," he says.

He really does believe in the possibility

of church growth, even though he is realistic about the fact of decline

and the danger, on present trends, of complete collapse. Asked about the

thesis that

religion

is now a toxic brand, especially to the young, he says: "A lot depends

on how you ask the question. We've got a lot of churches with loads of

young people, but I half accept the premise … there is an element of

toxicity in the brand with some people. What's absolutely essential is

to demonstrate and talk about the love and goodness of Christ and how he

reaches out to people, rather than telling people how to behave."

The

trouble is that most of his church still supposes that telling people

how to behave is the best part of Christianity and telling other

Christians how to behave is quite the most enjoyable part. The schism

over homosexuality looks impossible to heal. HTB used to be implacably

opposed, as it once was opposed to divorce, but now has moved to a

position of pained silence. Welby himself was profoundly shocked by the

reaction to his opposition to gay marriage in the House of Lords. Now he

says that the fight is over: "The church has reacted by fully accepting

that it's the law, and should react on Saturday by continuing to

demonstrate, in word and action, the love of Christ for every human

being."

But in Africa the movement has been sharply the other way.

People around the archbishop are horrified by reports that two

suspected gay men have been burned alive by mobs in Uganda who were

celebrating the passage of an anti-gay law enthusiastically supported by

the Ugandan Anglican church. But there is no pressure that he can apply

that does not risk being dismissed as neocolonial interference.

The African opponents of gay people have coalesced into an alternative version of the Anglican Communion, called

Gafcon.

This has close connections with parts of the HTB movement that are

planning to split from the Church of England formally if it moves

towards open recognition of gay relationships. Welby himself spoke to

the Gafcon primates before their most recent meeting, but did not attend

it. He assured them of his admiration for their courage and that he had

listened carefully to their view on sexuality.

In its studied

absence of guile, this was reminiscent of De Gaulle telling the Algerian

settlers that he had heard them – which they, to their cost,

misunderstood as saying he had joined their side. Welby has not joined

either side in the debate quite yet. Some clergy will undoubtedly marry

their same-sex partners, despite the orders from bishops – among them

Welby – that they refrain from doing so. But the discipline in those

cases will be a matter for the individual bishops. The archbishop has

positioned himself a little above the fray. This is characteristically

diplomatic and realistic, as no one knows whether there are in fact

legal ways to punish vicars who marry legally.

But it is also part of his belief that Christians ought to be able to "disagree well together".

The

job of archbishop of Canterbury is of course impossible. Welby sleeps

six hours a night (if that), he travels relentlessly, and his diary is

crammed: for this article he could talk for 10 minutes on the telephone,

booked 10 days in advance. No one I spoke to who had worked with him

did not trust him, but no one felt they knew him, either. He is in the

establishment now, but not on its side, despite his privileged

background – or perhaps because of it. His commitment to the poor and to

the victims of loan sharking made a huge impression in Durham. But

perhaps he is not so very far from his roots after all.

This mild

man is oddly reminiscent of General Conyers, a character created by the

rather more conventional Etonian Anthony Powell: "He was a man who gave

the impression, rightly or wrongly, that he would stop at nothing. If he

decided to kill you, he would kill you; if he thought it sufficient to

knock you down, he would knock you down: if a mere reprimand was all

required, he would confine himself to a reprimand. In addition to this,

he patently maintained a good-humoured, well-mannered awareness of the

inherent failings of human nature: the ultimate futility of all human

effort."

Except, of course, that archbishops do not nowadays kill

anyone, and Welby is sure that human effort is not in fact ultimately

futile, because God notices and pities it.

• This article was

amended on 18 April 2014. The earlier version said Justin Welby's first

parish was a working-class suburb of Coventry, and that he remained

based in the city for 10 years. His first parish was within the Coventry

diocese, but in Nuneaton.