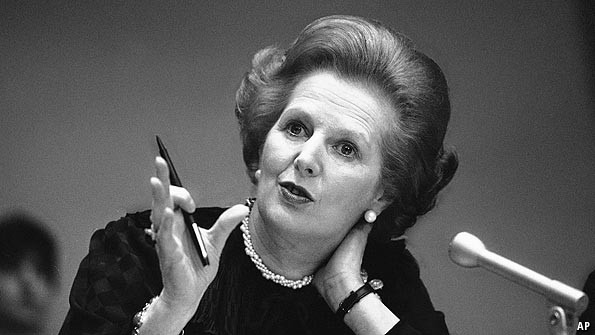

Margaret Thatcher

The lady who changed the world

The essence of Thatcherism was to oppose the status quo and bet on freedom—odd, since as a prim control freak, she was in some ways the embodiment of conservatism. She thought nations could become great only if individuals were set free. Her struggles had a theme: the right of individuals to run their own lives, as free as possible from the micromanagement of the state.

In Britain her battles with the left—especially the miners—gave her a reputation as a blue-rinse Boadicea. But she was just as willing to clobber her own side, sidelining old-fashioned Tory “wets” and unleashing her creed on conservative strongholds, notably the “big bang” in the City of London. Many of her pithiest putdowns were directed towards her own side: “U turn if you want to”, she told the Conservatives as unemployment passed 2m, “The lady’s not for turning.”

Paradoxes abound. Mrs Thatcher was a true Blue Tory who marginalised the Tory Party for a generation. The Tories ceased to be a national party, retreating to the south and the suburbs and all but dying off in Scotland, Wales and the northern cities. Tony Blair profited more from the Thatcher revolution than John Major, her successor: with the trade unions emasculated and the left discredited, he was able to remodel his party and sell it triumphantly to Middle England. His huge majority in 1997 ushered in 13 years of New Labour rule.

Yet her achievements cannot be gainsaid. She reversed what her mentor, Keith Joseph, liked to call “the ratchet effect”, whereby the state was rewarded for its failures with yet more power. With the brief exception of the emergency measures taken in the wake of the financial crisis of 2007-08, there have been no moves to renationalise industries or to resume a policy of picking winners. Thanks to her, the centre of gravity of British politics moved dramatically to the right. The New Labourites of the 1990s concluded that they could rescue the Labour Party from ruin only by adopting the central tenets of Thatcherism. “The presumption should be that economic activity is best left to the private sector,” declared Mr Blair. Neither he nor his successors would dream of reverting to the days of nationalisation and unfettered union power.

On the world stage, too, Mrs Thatcher continues to cast a long shadow. Her combination of ideological certainty and global prominence ensured that Britain played a role in the collapse of the Soviet Union that was disproportionate to its weight in the world. Mrs Thatcher was the first British politician since Winston Churchill to be taken seriously by the leaders of all the major powers. She was a heroine to opposition politicians in eastern Europe. Her willingness to stand shoulder to shoulder with “dear Ronnie” to block Soviet expansionism helped to promote new thinking in the Kremlin. But her insistence that Mikhail Gorbachev was a man with whom the West could do business also helped to end the cold war.

The post-communist countries embraced her revolution heartily: by 1996 Russia had privatised some 18,000 industrial enterprises. India dismantled the licence Raj—a legacy of British Fabianism—and unleashed a cavalcade of successful companies. Across Latin America governments embraced market liberalisation. Whether they managed well or badly, all of them looked to the British example.

But today, the pendulum is swinging dangerously away from the principles Mrs Thatcher espoused. In most of the rich world, the state’s share of the economy has grown sharply in recent years. Regulations—excessive, as well as necessary—are tying up the private sector. Businessmen are under scrutiny as they have not been for 30 years. Demonstrators protest against the very existence of the banking industry. And with the rise of China, state control, not economic liberalism, is being hailed as a model for emerging countries.

For a world in desperate need of growth, this is the wrong direction to head in. Europe will never thrive until it frees up its markets. America will throttle its recovery unless it avoids over-regulation. China will not sustain its success unless it starts to liberalise. This is a crucial time to hang on to Margaret Thatcher’s central perception—that for countries to flourish, people need to push back against the advance of the state. What the world needs now is more Thatcherism, not less.

-

Margaret Thatcher prepares for victory in the 1983 general electionGetty Images

Margaret Thatcher prepares for victory in the 1983 general electionGetty Images -

As Margaret Roberts, a grocer's daughter, she checks the price and quality of goods in 1950s Dartford, where she is standing for electionAP

As Margaret Roberts, a grocer's daughter, she checks the price and quality of goods in 1950s Dartford, where she is standing for electionAP

1 / 12