IN THIS week's print edition we

looked at a new report which suggested that Britain’s tourist industry could help boost its regional economies.

New

research published on November 21st by Deloitte, a consultancy, has

raised hopes that tourism can help Britain’s regions reduce their

reliance on other industries. It predicts that the sector will grow by

3.8% a year between now and 2025—much faster than manufacturing, retail

or construction. Tourism, it says, has been Britain’s fastest-growing

employment sector since 2010. Unusually, northern England, Wales, and

rural Scotland—areas which otherwise struggle to attract new

businesses—have recently seen particularly strong job growth.

The

report also stresses the importance of tourism to the wider British

economy. Deloitte estimates that the tourism industry, and its supply

chain, already produces 9% of Britain’s GDP. And it forecasts that this

will steadily grow to 10% of output over the next decade or so. Between

2010 and 2012 alone, one-third of new jobs created in the British

economy were generated by the tourism industry, around 150,000 in total.

However,

the report forecasts that the balance between Britons and foreigners

using Britain's visitor facilities will change over time. Spending by

foreign visitors, the report forecasts, will grow by over 6% a year,

with spending by Britons holidaying at home rising by only about 3%, in

comparison.

Saying which parts of Britain will benefit most—and

lose out most—from this change is a difficult question. London will

surely benefit; 53% of spending by foreign visitors already takes place

there. However, what will happen in Britain’s other regions will be much

less predictable.

Some dramatic shifts in the geography of

Britain’s tourism economy are already underway. Nationally, the outlook

for the industry is healthy. Spending by foreign visitors in Britain

reached record levels in July, according to the Office for National

Statistics and the number of jobs in the sector is still increasing. In

contrast to the widening gap between the prospering south and the

depressed north in the rest of the economy, the tourism industry north

of the River Trent and west of the River Severn appears to be booming.

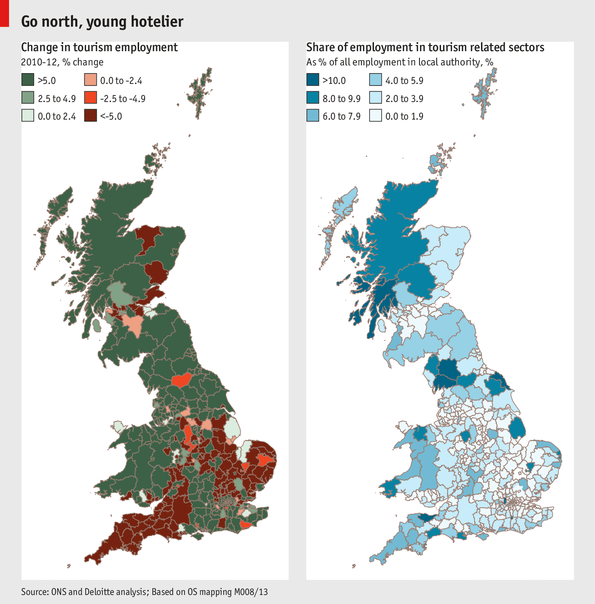

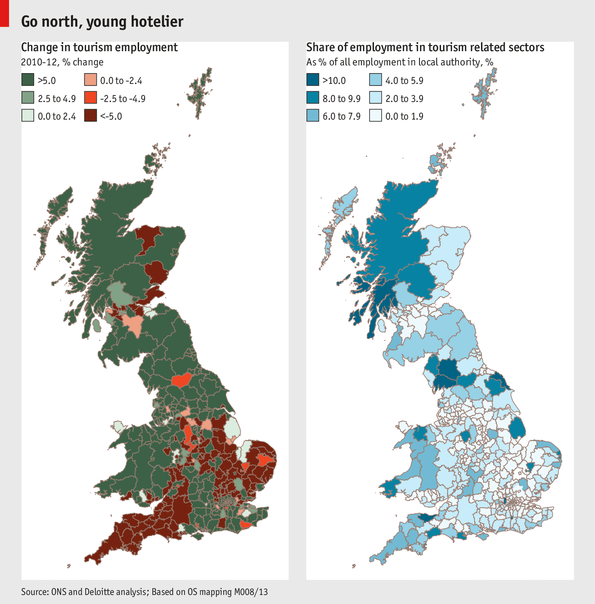

However, according to data produced by Deloitte showing where jobs were

gained and lost in the tourism sector between 2010 and 2012, many parts

of the south-west, East Anglia, and East Anglia lost over 5% of their

tourism-related employment in this period (see maps).

But the average hides several areas that did much worse than

this. Just north of London, Harlow and St Albans in Hertfordshire lost

51% and 40% of their tourism-related jobs. More worryingly, places where

tourism accounts for the high percentage of total employment also did

badly. Cornwall, where tourism provides 7% of jobs, lost 17%, and the

Isles of Scilly, where it accounts for 15%, lost a whopping 43%.

In

contrast, the number of tourism-related jobs rose strongly in London

(boosted by the 2012 Olympics games) and in Wales, rural Scotland and

northern England. Even in grimy Stockton-on-Tees, the number of jobs

went up by 103%, and in rather unpicturesque Barking and Dagenham in

London by 95%.

In part, this rather strange pattern—London and

“outer” Britain doing particularly well—is due to the economy as a whole

doing well. Holiday makers in the south-west and East Anglia—the areas

that have done worst in terms of employment—tend to be the places

Britons from the south-east tend to go on holiday to. As British

consumer confidence has returned over the last few years, it seems that

they are rediscovering a taste for short-haul travel abroad again.

Foreign tourists appear to have been unable to make up the shortfall

from Britons going to places with better weather—visitors from

abroad tending to be more attracted to places like London, Edinburgh and

the quaint scenery of Wales and Scotland instead.

But it remains

to be seen whether places like Cornwall can attract foreign tourists,

over the horizon of Deloitte's report, to replace the Britons who now

holiday elsewhere. Although it may be too soon to judge whether the

benefits of Britain’s booming tourism industry can be spread equally

throughout its regions, looking at the most recent trends, this seems

exceedingly unlikely.

文 / 鄭貞文

文 / 鄭貞文