- Election 2015

- 1118

The main party leaders are criss-crossing the UK appealing to undecided voters in key seats as the election campaign enters its final two days.

Conservative leader David Cameron has warned a SNP-backed Labour government was a "chilling prospect" as he appeared with Boris Johnson in London.

Ed Miliband said Labour would "rescue" NHS hospitals from "savage" budget cuts under a Conservative government.

Nick Clegg said the Lib Dems would "guarantee stability" after 7 May.

UKIP leader Nigel Farage is spending the day in the Kent seat he hopes to win for his party, after taking out a two-page advertisement in the Daily Telegraph urging people "to vote with their heart".

In other election news, with two days to go before polling day:

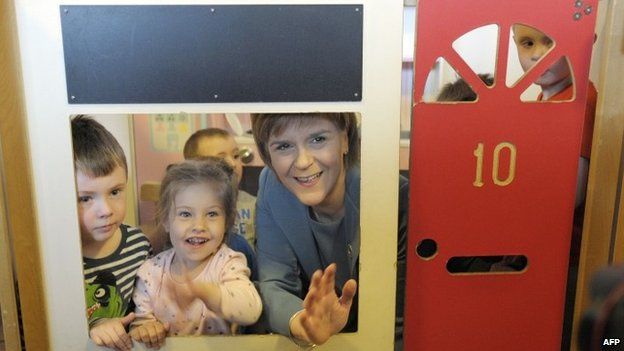

- SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon questioned the legitimacy of a UK government which did not include Scottish MPs

- The Green Party, which is hoping to retain its one parliamentary seat, promises to scrap work capability assessments - and also urges voters to "send a message" on climate change in Thursday's poll

- Conservative Work and Pensions Secretary Iain Duncan Smith said voting UKIPwas "like a suicide note" for hopes of an EU referendum while Nick Clegg said areferendum is not a coalition "red line" for the Lib Dems

- The head of the Bow Group conservative think tank has endorsed leading UKIP candidates

- The vice-chair of Labour's general election campaign, Lucy Powell, has denied suggesting Ed Miliband could break his election pledges.

- The Independent says it was backing a continuation of the Conservative-Lib Dem coalition

Polls suggest the election is still too close to call, and in the final days the parties are focusing on their core messages amid speculation about post-election deals if there is a hung Parliament.

Policy guide: Key priorities

What are the top issues for each political party at the 2015 general election?

Labour has been campaigning on the NHS, publishing what it calls a leaked document showing the cash deficits of some hospital trusts.

The figures come from a group called NHS Providers, which represents and lobbies for NHS trusts.

Labour said 98 of England's 240 trusts expected to have run up deficits by next April of more than £750m between them. The total NHS budget is more than £100bn.

Speaking in the target seat of Bedford, Mr Miliband said the NHS was facing a "financial bombshell", which would result in two-thirds of hospitals having to make substantial cuts this year. Only a Labour government could "rescue" the health service, he claimed.

Appealing to undecided voters as he seeks to improve on the 258 seats his party won in 2010, the Labour leader said the election would be "the closest we have ever seen in our history".

Mr Cameron told BBC Radio 5 live that the NHS had made "real progress" in the past five years and his party was committed to providing the money that hospitals need to meet the growing demands they face and to go on treating more patients.

"We have put the money in, we have got rid of bureaucracy which has kept money on the front line but people in the NHS have worked incredibly hard to deliver this service," he said. "The key thing for the future is to make sure we have the strong economy that can support the strong NHS."

Analysis by political editor Nick Robinson

By 10 o'clock on Thursday evening the people will have spoken but the questions which will then follow look likely to be - "What on earth did they mean by that? Who actually won? Who has the right to govern?"

Unless the polls are wrong - which they very well might be - and unless there is a late switch in opinion - which there still could be - most players and pundits are now expecting an election that is too close to call and may produce a result which could allow for either David Cameron or Ed Miliband to become prime minister.

So, what is obsessing politicians of all parties behind-the-scenes is the debate about what a legitimate government would look like.

The Conservatives, which won 307 seats in 2010, are targeting seats held by Liberal Democrats, as well as appealing to UKIP supporters and Conservatives who might not bother to go to the polling station, in an attempt to win an overall majority.

While SNP MPs were perfectly entitled to make their voice heard in Westminster, Mr Cameron told the BBC it would be "unhealthy" for a future government to be reliant on a party that "did not want the UK to be a success".

Mr Clegg said his party would do a "lot better" than commentators were suggesting as he launched a 1,000 mile "dash" from Land's End to John O'Groats, taking in key marginal seats in Cornwall, Somerset, South Wales and the Midlands.

Opinion polls suggest the party could lose up to half of the 57 seats it won five years ago.

Amid speculation about possible coalition deals in the event of another hung Parliament, Mr Clegg said the party with the "greatest mandate" in terms of seats and votes won should have the "space and time to try and assemble a government".

The Lib Dems, he told Radio 4's Today programme, would be prepared to talk to other parties - except UKIP and the SNP - in a "grown-up" way, saying they would be "guarantors of stability at a time of great uncertainty".

The best of BBC News' Election 2015 specials

Over one in ten people who voted Conservative in 2010 have since left the party for UKIP, which detests the European Union and immigration. The defectors are typically male, white and working-class. The Conservatives have not achieved the long-expected “crossover” with Labour in the polls mainly because it has not squeezed UKIP enoughhttp://econ.st/1AoG8qg

Wooing white-van man

The Tory party badly needs working-class votes to hold on to power

COMMUTERS on the A414 in Essex have recently become used to a curious sight. Every day between 7am and 9am, then again from 4pm to 7pm, a man in a peaked cap perches on a small chair by the dual carriageway, beams at the oncoming traffic and gives drivers the thumbs-up sign. “You have to look them in the eyes,” explains Robert Halfon, the Conservative MP for Harlow in Essex. Many of the drivers return the thumbs-up gesture and honk their horns. “Halfon, yeah!” shouts one man, leaning out of the window of his van as it speeds past.

Mr Halfon is no ordinary MP. He has won admirers from across the political spectrum by fighting a series of campaigns on consumer issues, from taxes on bingo halls to surcharges on electricity bills. He is best known for persuading the Tory-Liberal Democrat coalition government to cancel every planned fuel-duty increase since 2010. The MP calls his brand of politics “white-van Conservatism”—a reference to the aspirational working-class voters who make towns like Harlow, north-east of London, such crucial bellwethers. They voted for Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s and Tony Blair in the 1990s. But this time they are proving especially hard to woo.

The Tories can point to a rebounding economy and an increasingly popular leader in David Cameron (see timeline). But with a week to go before the general election on May 7th, they are tied with the opposition Labour Party, as they have been throughout the campaign. In order to form another coalition with the Lib Dems, the Tories must hold almost all of their seats in the House of Commons. Oddly, the greatest challenge to their continued rule does not come directly from Labour: over the course of this parliament few voters have moved from the Conservative camp to the Labour one, or vice versa. The Tories’ real problem is the populist UK Independence Party (UKIP) and its strong appeal to white-van man.

Over one in ten people who voted Conservative in 2010 have since left the party for UKIP, which detests the European Union and immigration. The defectors are typically male, white and working-class. Lynton Crosby, the Tories’ campaign chief, reckons that the party’s typical target voter earns about £15,000 ($23,000) a year—40% less than the national average—reads the Sun on Sunday, a right-wing tabloid, and values economic and national security above all else.

This analysis colours the entire Conservative campaign. In an interview on April 6th Mr Cameron urged UKIP voters to “come home”. At the party’s manifesto launch on April 14th, he described the Tories as “the real party of working people”. Two weeks later he called it the party of “the grafters and the roofers and the retailers and the plumbers”. He talks endlessly about security.

The Tories have courted white-van man in their manifesto and in the promises they have made on the campaign trail. The prime minister has pledged to create 50,000 new apprenticeships, expand free child care and take those earning the minimum wage out of income tax. He even promises to legislate against any increases in the government’s main revenue-raising taxes until 2020. He has revived Margaret Thatcher’s totemic bid for working-class support by promising to extend the “right to buy” social housing to tenants of housing associations.

The pursuit of van-driving voters also partly accounts for the Conservatives’ frequent dire warnings about the risk to Britain’s economic and political stability of a Labour government propped up by the separatist, left-wing Scottish National Party. Polls suggest UKIP supporters worry more about this than most.

Stuck in a lay-by

Mr Halfon reports that voters are now raising the issue on the doorsteps. He declares himself delighted at his party’s campaign; after the election, he plans to frame the newspaper coverage of its manifesto. On April 30th the Sun newspaper endorsed the Tories—though, muddling the message, its Scottish edition went for the SNP. Yet the Tories’ white-van-man strategy is not yet working well enough. The party has not achieved the long-expected “crossover” with Labour in the polls mainly because it has not squeezed UKIP enough. The insurgent party remains on around 12%, up from just 3% in 2010. Matthew Goodwin, an expert on UKIP, estimates that the party could indirectly cost the Tories around 30 seats. Labour must pick up about 40 English seats to lead the next government.

The best explanation is that many voters still doubt that the Conservatives understand their lives and interests. Mr Cameron takes no pains to hide his poshness. And at times the party has helped to reinforce this sense: from its chief whip swearing at a policeman (allegedly calling him a “pleb”) to the economically savvy but politically masochistic decision to cut income tax on the highest earners in the “omnishambles” 2012 budget.

More damagingly, low-income voters are not feeling better off than they did in 2010. Though unemployment has fallen steeply, this is partly the flipside of insecure work and stagnant wages. Tories protest, with reason, that low wages are better than none at all—and that at least things are not going backwards. But the van drivers can be forgiven for not being overwhelmed with gratitude to the governing party. As Mr Halfon’s roadside vigil demonstrates, it can take extraordinary efforts to persuade such voters that Conservative MPs are truly on their side.

沒有留言:

張貼留言